By Peter Tormey (Article originally posted by Gonzaga University News Service.)

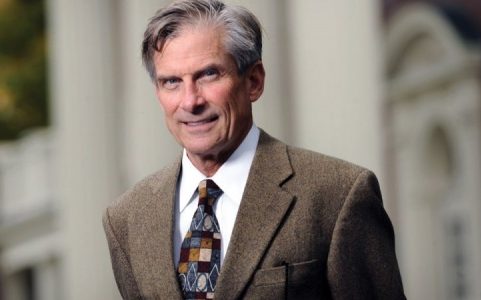

SPOKANE, Wash. – William D. Adams, chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, told a packed crowd in Cataldo Hall on Monday night how the study of the humanities helped him make sense of his experience as a veteran of the Vietnam War and how it can help other veterans.

In the lecture sponsored by Gonzaga University’s new Center for Public Humanities, Adams relayed his own experience to underscore the “profoundly connected” ways that an individual story and a nation’s collective narrative converge for veterans and how the humanities can help them make sense of their experiences.

Adams said he enlisted in the Army in the summer following his freshman year at Colorado College.

“That was the beginning of a three-year experience that was more complicated, more intense, more interesting and more varied than anything I had ever experienced in my life,” said Adams, who graduated from officer candidate school before being sent in 1968 to a remote part of the Mekong Delta.

After what he described as an “enormously difficult, complicated but extraordinarily interesting year,” Adams survived and returned to the United States in late spring of 1969. The day after being discharged from the Army, Adams went to the University of California at Berkeley campus and experienced one of the most cataclysmic moments in the anti-war movement with a demonstration at People’s Park. With police and National Guard troops on the ground and helicopters overhead, “we decided it was better to not be there,” said Adams who returned to San Francisco with friends. Later, they learned that student James Rector had been shot to death.

“I was pretty much at a total loss to understand what was happening in my country. That experience of seeing the country coming unglued right in front of me added to a level of confusion and struggle,” he said.

Adams enrolled at University of Michigan where he studied philosophy, psychology and art history and discovered there was no escaping the anti-war movement. He returned to Colorado College in the fall of 1969 and struggled to reconcile his personal war experience with the nation’s collective narrative.

“It was about trying to understand what had happened to me in Vietnam and how that experience had affected me and how it had changed me,” he said. “I knew it had affected me in powerful ways. I think, quite understandably, people talk about combat and the experience of war as one of extraordinary intensity.”

The virtually indescribable intensity of combat both illuminates and confuses veterans, he said.

“There’s a kind of brilliant clarity to these experiences, but they also are profoundly confusing,” he said. “I was left with a residue of questions: about who I was, about what had become of me, about how these experiences had changed me, about whether or not these experiences had diminished me or made me better in some way, and about how I was going to sort out this journey and make sense of it.”

One central aspect of a veteran’s individual challenge with war, he said, is coming to terms with the problem of “moral injury” or the ways in which the experience of violence affects and changes both its victims and perpetrators. Another powerful dimension involves the good things veterans experience that were also extraordinary, intense and involve a deep identification with and connection to comrades.

Adams explained how J. Glenn Gray, a philosophy professor of his at Colorado College, demonstrated – through the way he lived and his work – a path to personal integration after war. A World War II veteran, Gray wrote “The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle,” which Adams called an extraordinary book about the experience of war.

“It changed my life in this way: I became aware of how I could get perspective on my experience by way of his reflections on his own experience,” Adams said. “It taught me how these resources, these literary resources in the humanities, can help us see ourselves with a little bit of distance and that’s the key. It’s seeing yourself by way of something else, which is powerful because sometimes the unmediated information or material is just too difficult, too intense or too close.”