By Kate Vanskike

Roger Johnson should have walked the commencement stage in 1966, but that didn’t happen until nearly 50 years later.

While at Gonzaga, studying psychology, Roger Johnson was part of the Army ROTC program, where he says he had “wonderful training under an excellent military professor.” (Major Clem)

The conflict in Vietnam was broiling and Johnson wanted to know more about what was taking place. He says, “I was given the inquisitive search of knowledge, as the Jesuits would say.”

He studied the history of Vietnam, and read the book “How We Won the War” on Guerilla warfare by Vo Nguyen Giap, the Commanding General of the North Vietnamese Army, seeking to understand all he could of military science. When the time came to put his knowledge to use, Johnson found he was “better prepared and had a much better understanding than most senior and junior officers.”

Johnson deferred his studies at Gonzaga in order to graduate in January 1966. As a ROTC Distinguished Military Graduate, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant, Regular Army, into active military duty. (Deferring his graduation put him in front of the West Point class of 1966, granting him a better chance of plumb assignments, and one more winter ski season.) That winter, instead of entering the workforce with a fresh degree, Johnson would leave the snow-laden campus of Gonzaga for Fort Benning, Georgia, where he completed the Infantry Officer Basic Course and trained as a paratrooper, earning his Jump Wings at the US Army Airborne School, learning to jump from planes in a time of war. Prior to reporting to the 101st Airborne Division at Ft. Campbell, Kentucky, he completed the Officer Communications Course at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma.

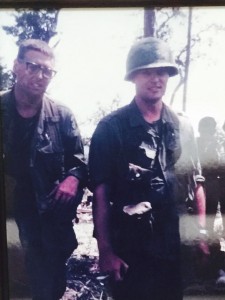

Reporting to the 101st Airborne Division, he was assigned as an Assistant Battalion Operations Officer and Battalion Communications Officer. (2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry, Airborne) Subsequently, he became a Rifle Platoon Leader. While at Ft. Campbell, he graduated from Jumpmaster School and received his Jumpmaster designation as well. Receiving order to Viet Nam to become an Advisor, he reported to the US Army Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg, NC, and completed the Military Assistant’s Advisory (MATA) course. When he eventually landed in Viet Nam in October, 1976, he served as an infantry Battalion Adviser to the Army Republic of Viet Nam (AVRN), providing guidance in tactics, air support for combat operations, medical evaluations, resupply, artillery, and intelligence.

He was proud to have rank over West Point graduates and to land assignments such as communications officer and rifle platoon leader. He also attended a special warfare school at Fort Bragg and completed a military assistant’s training advisory course. When he eventually landed in Viet Nam in 1967, he served as an adviser to the Army Republic of Vietnam infantry, providing guidance in air support for combat, medical evacuations, resupply, artillery and more.

Foxholes and Live Grenades

Like so many other veterans of the Viet Nam War, Johnson can recall every horrific detail of his time on the ground. On one particular Search and Destroy mission, November 14, 1967, in the Central Highlands, he learned, after a vicious ambush, that the North Vietnamese Army was his area of operation. (The NVA were secretly deploying for the Tet Offensive, on 31 January 1968.)

“I was ambushed in a search-and-destroy op by the North Vietnamese,” he shares. “My counterpart bled to death next to me, my helmet was blown off, bombs went off and I remember it showering down on us.”

“After Huey UH-1D helicopters inserted us on a hot LZ (Landing Zone) at 1130 Hours, we conducted ground sweeps looking for the enemy. At 1515 Hours our company was ambushed by a superior force. A vicious fire flight ensured. Bullets were dancing in the ground, as in a surreal slow motion movie. I called for artillery support but we could not sport our rounds in the jungle. Approximately 20 minutes later 2 UH-18 helicopter gunships arrived at our location. Both were shot down on their second pass providing air support.”

“After about 20 minutes, the Vietnamese 1st Lieutenant Company Commander began to maneuver his unit, I heard a swishing sound. When I came to, my counterpart, wounded in the stomach, bled to death beside me. I had been wounded in the head from the 8-40 rocket shrapnel. My first thought was: “You are an American Lieutenant, take charge of this situation.”

I called a USAF (FAC) Forward Air Controller on my PRC-25 radio and asked if he had any ordinance on the station. He said he had an F-100 with two 250 lb bombs. I asked him to drop them on our position, as we were being overrun. When the bombs went off I remember dirt, rock, tree limbs and other debris showering down on us. Fortunately, we were just out of the kill zone. All action ceased.”

He kept his wits about him. “I quickly formed a wagon wheel perimeter in the jungle with the remaining soldiers, putting a machine gun at a likely avenue of approach, placed the severely wounded and KIA in the center, and ordered the soldiers to dig fox holes. It becomes dark early in the jungle, it was 1630 Hours, our planned time of extraction. The remaining Vietnamese battalion was inserted into our pre-designated extraction point in order to support us, however the Battalion Commander refused to move through the jungle at night.”

Johnson remembers digging foxholes, walking from wounded to wounded, watching a C-130 Spooky illuminated by the moon, waiting for rescue. That night, the enemy fired on his position and the Vietnamese who could ran. They were captured. An enemy patrol walked through their perimeter, one nearly stepping into his foxhole. Another, silhouetted against the moonlit sky, wore the helmet of an NVA; his first hint that these were North Vietnamese Regular soldiers.

A few hours later, his American NCO and he attempted to escape and evade back to the extraction zone. Soon they confronted a squad walking perpendicular to them on patrol. The patrol was on a hillside slightly above them when the C-130 dropped a flare. Exposed by the flare, he didn’t want his own men firing on them. All were wearing soft hats. In Vietnamese, he said: “Lieutenant Johnson, American advisor.” They all turned around firing AK-47s.” After a brief fire fight, his M-1 Carbine jammed and his NCO ran out of ammunition. They darted into the jungle underbrush and dropped to the ground. Johnson pulled a grenade from his ammo belt and pulled the pin. They waited, and soon 2 NVA soldiers walked past them, one on each side. They went undetected.

After about an hour, Johnson moved their position to one of the bomb craters, still holding the live grenade. They could hear the NVA moving about, checking the dead, collecting weapons, and speaking to one another. Holding the live grenade in his left hand, he clicked his radio handset with his right hand. The C-130 pilot answered his call sign. Johnson gave a click and the pilot answered; I hear a click. “Give me one click for affirmative and two clicks for negative.” The pilot asked questions for the next hour with Johnson clicking once or twice, describing the scene, until the aircraft ran low on fuel and departed. He held the live grenade all night, moving it from hand to hand. (Lesson, don’t drop the pin!)

At dawn, Johnson counted over 450 NVA moving out in single file.

He remembers that only 27 men remained from the original 125 South Vietnamese company. And he remembers the date – November 13, 1967 – when the Vietnamese battalion arrived and later a med-evac ship arrived at 11:30 a.m. to med-evac the wounded and KIA.

After having shrapnel removed from his head at the field hospital, Johnson was asked to be the aide-de-camp for a new general. He remained in that role for about a year before returning to the U.S. in 1968.

Success and Gratification

Back at home, safe and sound, Johnson received numerous military honors, including the Combat Infantry Badge, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Air Medal, and more. He became a financial broker with giants like E.F. Hutton and A.G. Edwards, then founded his own wealth management company, Summa Global Advisors, LLC, in 2009.

“I attribute my success in the military and in life to my experience at Gonzaga,” Johnson says.

But even as a successful businessman, who is actively engaged in supporting his Oregon communities by serving on many boards to address education, crime and music, something was still missing from Johnson’s life. He had never walked the commencement stage at his alma mater.

Until May 10, 2015 – another date Johnson can etch in his memory.

On that day, a 70-year-old Viet Nam veteran and hero joined the 942 fresh-faced 20-somethings marching to the tune of “Pomp and Circumstance” at Gonzaga’s undergraduate commencement.

“It was very gratifying,” says Johnson. “To see all the young kids there, just starting out in adulthood. To listen to the speech. The whole sense of the graduation experience was very meaningful.”

“For me, it completed the full circle.”