Johnny Arlee, Storyteller, talks Hollywood and his efforts to preserve the language shared by several Native American tribes of the Inland Northwest

By Kate Vanskike

With help from Jennifer Childress (’91) who publishes children’s books in Salish

In the movies we watch, Hollywood takes plenty of creative license to depict people and places. Doing so has the potential to create a hullaballoo, misrepresenting cultures and their traditions, and perpetuating stereotypes about them. For some directors, though, accuracy is as important as the acting, and that means having an advisor on set.

The popular Western “Jeremiah Johnson,” filmed in 1972, starred Robert Redford as a mountain man who encountered members of the Crow, Blackfoot and Flathead (Salish) tribes. For a more accurate portrayal of the Salish people in the movie, its director, Sydney Pollack, hired a technical advisor to offer guidance. He chose Johnny Arlee, a member of the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation, and even gave him a speaking role.

“I’m the skinny Indian who jumps off a horse and yells at the guy with the scalps (Redford),” Arlee says. “Five days of filming for five minutes on the screen.”

His real job was to coach Delle Bolton, who played the chief’s daughter, to say her lines in Salish, but he found other opportunities to help make the scenes set among the Salish people more authentic.

In one scene, the script called for the chief to open his daughter’s mouth forcefully, tap at her teeth and say, “strong teeth.” The directors said it was meant to be funny, but Arlee said, “No, no. I’m not laughing. That’s offensive, for a man to open her mouth like that – especially a chief.”

They redid the scene with the chief only pointing to the daughter’s teeth instead of handling her physically.

On another day, Johnny was sitting in the director’s office when a props manager came in and announced that he had the chickens. “What are the chickens for?” Johnny asked, and the man explained that the Indians were farmers. Johnny was happy to provide some clarity: “We didn’t have any chickens! We were buffalo hunters! And, if chickens had been brought to the camp, they wouldn’t have lasted long with the dogs and the coyotes.” It suited Johnny just fine when later in the filming, the chickens got loose and flew up into the trees. “Typical Flathead chickens!” he laughed.

Still, being a part of the movie “was the highlight of my life,” says Arlee, not because of the bragging rights to having been on set with Robert Redford, but to have rediscovered his love for – and the importance of – his language.

Teach the Children

When “Jeremiah Johnson” eventually hit the big screen, Arlee sang a song in the movie. At its premiere showing in Missoula, girls from his local community showed an interest in learning to sing in Salish and to do traditional drumming.

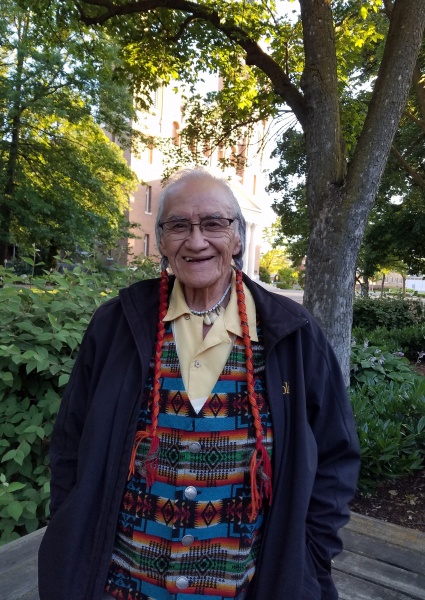

Johnny Arlee, during a 2016 visit to Gonzaga to celebrate the longstanding friendship between Northwest Native American peoples and the Jesuits.

“So I agreed to teach them,” Arlee says. It was that simple for him, even though elders thought it inappropriate to have girls drumming instead of the boys. When confronted, he said, “The boys are busy playing basketball and football. Until they want to learn their culture, the girls are learning.”

As he became devoted to that role, his hunger for more of the language of his ancestors only grew. Arlee once spent two weeks immersing himself in listening to 30 cassette tapes – each with 30 minutes of Salish elders telling stories – and translating them.

He used what he calls “the old father’s dictionary,” but sometimes, he still had to ask an elder to explain a word. One time, the story was about a young man sending a boy to get water. He would carry a bandolier of buffalo string attached to a buffalo horn dipper to fill with water. But there was a word being used to convey getting the water that Johnny didn’t know. “The elder said it again and I understood. The word was the actual sound that the cup made as it slurped up the water.”

It was an onomatopoeia – a word that makes the sound being described – and Salish has lots of them. (There is even a specific word for the sound feet make when crunching through the snow.) The next step for Johnny after providing oral translation was to work with the tribal culture committee to advocate the creation of a written language for Salish.

“In 1974, we had a linguist come, and I was just in awe of that work,” he says. They adopted the phonetics to provide each sound with a character.

For Posterity

Having a language preserved in writing is only half the battle for the Salish-speaking peoples, which include the coastal groups (Washington and Oregon as well as British Columbia, Canada) and interior groups throughout eastern Washington, northern Idaho, western Montana and British Columbia. These include the Spokane, Kalispel, Bitterroot Salish (Flathead), Colville, Okanogan and Coeur d’Alene.

“There was a time when the elders needed a translator for going to the doctor or shopping and other things,” Johnny says. “But they all seemed to pass at about the same time, and when they were gone, there wasn’t a need for Salish speakers anymore.”

By the ‘70s when Johnny’s interest in the language was piquing, only a handful of native speakers remained. (Native American languages are among the most endangered in the world.)

Today, there are about 100 new speakers and that number continues to grow. There are numerous language instruction programs for all ages on tribal lands as well as in cities and towns throughout the Inland Northwest, including Spokane. Tribal schools and some public schools offer courses in Salish languages from elementary school through the high school level and even as college courses. In several of those efforts, Johnny has been personally involved, providing course translations in everything from math to science.

Today, children in Salish communities play – and argue! – with each other completely in the Salish dialects of their people.

Maybe they’ll even learn the word for Flathead chicken.

Read about the longstanding friendship of Northwest Native American peoples with the Jesuits, as featured in Gonzaga Magazine.